Years of scientific research have clearly established that particle pollution and ozone are a threat to human health at every stage of life, increasing the risk of premature birth, causing or worsening lung and heart disease, and shortening lives. Some groups of people are more at risk of illness and death than others, because they are more likely to be exposed, or are more vulnerable to health harm, or often both.

Air pollution can harm children and adults in many ways

Respiratory

- Wheezing and coughing

- Shortness of breath

- Asthma attacks

- Worsening COPD

- Lung cancer

Other

- Premature death

- Susceptibility to infections

- Heart attacks and strokes

- Impaired cognitive functioning

- Metabolic disorders

- Preterm births and low birth weight

Health Effects of Particle Pollution

Particle pollution – also known as particulate matter or soot – is a deadly and growing threat to public health in communities around the country. The more researchers learn about the health effects of particle pollution, the more dangerous it is recognized to be.

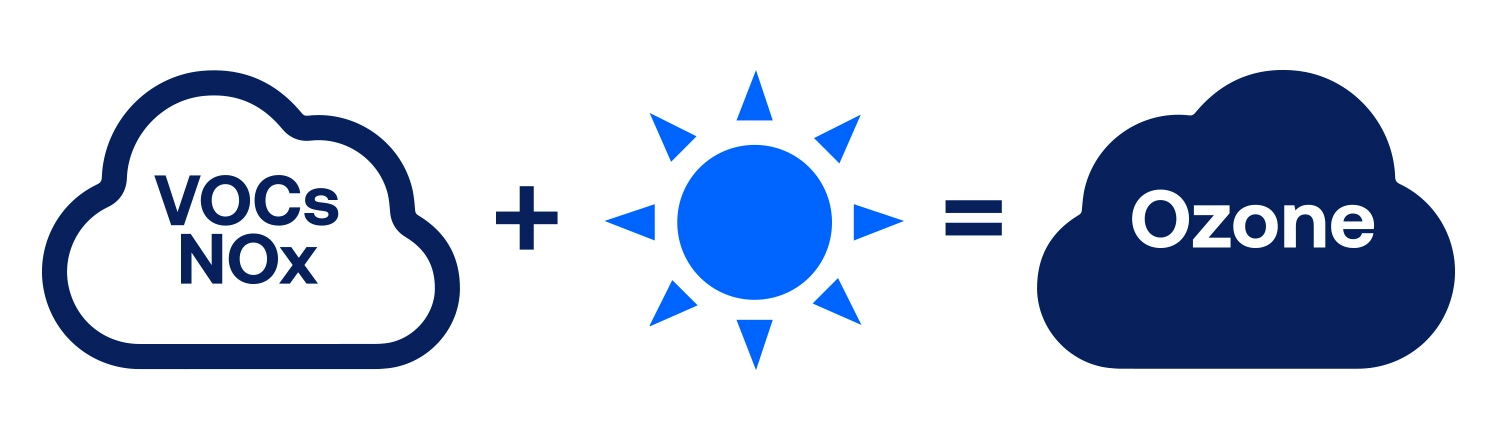

Health Effects of Ozone Pollution

Ground-level ozone, sometimes known as smog, is one of the most widespread and dangerous pollutants in the United States. Scientists have studied the effects of ozone on human health for decades. Hundreds of studies have confirmed that ozone harms people at levels currently found in many parts of the United States.

People at Risk

The health burden of air pollution is not evenly shared. Some people are more at risk of illness and death from air pollution than others. Several key factors affect an individual’s level of risk:

- Exposure – Where someone lives, where they go to school and where they work makes a big difference in how much air pollution they breathe. In general, the higher the exposure, the greater the risk of harm.

- Susceptibility – Individuals who are pregnant and their fetuses, children, older adults and people living with chronic conditions, especially heart and lung disease, may be physically more susceptible to the health impacts of air pollution than other adults.

- Access to healthcare – Whether or not a person has health coverage, a healthcare provider, and access to linguistically and culturally appropriate health information may influence their overall health status and how they are impacted by environmental stressors like air pollution.

- Psychosocial stress – There is increasing evidence that non-physical stressors such as poverty, racial/ethnic discrimination and residency status can amplify the harmful effects of air pollution.

These risk factors are not mutually exclusive and often interact in ways that lead to significant health inequities among subgroups of the population. Taken all together, these high-risk categories account for a large proportion of the U.S. population.

-

Health Effects Institute. State of Global Air. Boston, MA. 2024.

-

U.S. EPA. Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter. December 2019 EPA/600/R-19/188. Section 11.1.

-

Liu C, Chen R, Sera RF, Vicedo‑Cabrera AM, Guo Y, Tong S, Coelho MSZS, Saldiva PHN, Lavigne E, Matus P, Valdes Ortega PN, Osorio Garcia S, Pascal M, Stafoggia M, Scortichini M, Hashizume M, Honda Y, Hurtado‑Diaz M, Cruz J, Nunes B, Teixeira JP, Kim H, Tobias A, Íñiguez C, Forsberg B, Åström C, Ragettli MS, Guo Y-L, Chen B-Y, Bell ML, Wright CY, Scovronick N, Garland RM, Milojevic A, Kyselý J, Urban A, Orru H, Indermitte E, Jaakkola JJK, Ryti NRI, Katsouyanni K, Analitis A, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J, Chen J, Wu T, Cohen A, Gasparrini A, Kan H. Ambient Particulate Air Pollution and Daily Mortality in 652 Cities. N Engl J Med. 2019; 381(8):705-15.

-

Di Q, Dai L, Wang Y, Zanobetti A, Choirat C, Schwartz JD, Dominici F. Association of Short-Term Exposure to Air Pollution with Mortality in Older Adults. JAMA. 2017; 318:2446-2456.

-

Schwartz J, Fong K and Zanobetti A. A national multicity analysis of the causal effect of local pollution, NO2, and PM2.5 on mortality. Environ Health Perspect. 2018; 126(8):087004-1- 087004-10.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 9.1.2.6.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 6.1.2.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 5.1.2.1.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 5.1.2.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 5.1.2.2.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 11.2.

-

Pope CA, Lefler JS, Ezzati M, Higbee JD, Marshall JD, Kim S, Bechle M, Gilliat KS, Vernon SE, Robinson AL, Burnett RT. Mortality risk and fine particulate pollution in a large, representative cohort of U.S. Adults. Environ Health Perspect. 2019; 127(7):077007-1-077007-9.

-

Wu X, Braun D, Schwartz J, Kioumourtzoglou MA, Dominici F. Evaluating the impact of long-term exposure to fine particulate matter on mortality among the elderly. Sci Adv. 2020; 6.

-

Bekkar B, Pacheco S, Basu R, DeNicola N_Association of air pollution and heat exposure with preterm birth, low birth weight and stillbirth in the U.S.: A systemic review. JAMA Network Open. 2020; 3(6):e208243.

-

Bekkar B et al. 2020.

-

Ni Y, Loftus CT, Szpiro AA, Young MT, Hazlehurst MF, Murphy LE, Tylavsky FA, Mason WA, LeWinn KZ, Sathyanarayana S, Barrett ES, Bush NR, Karr CJ. Associations of pre- and postnatal air pollution exposures with child behavioral problems and cognitive performance: A U.S. multi-cohort study. Environ Health Perspect. 2022; 130(6).

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 5.2.2.2.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 5.2.3.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 6.2.2.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 5.2.5.

-

Liu F, Chen G, Huo W, Wang C, Liu S, Li N, Mao S, Hou Y, Lu Y, Xiang H. Associations between long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Pollut. 2019; 252(ptB):1235–1245.

-

Wu Y, Zhang S, Qian SE, Cai M, Li H, Wang C, Zou H, Chen H, Vaughn MG, McMillin SE, Lin H. Ambient air pollution associated with incidence and dynamic progression of type 2 diabetes: a trajectory analysis of a population‑based cohort. BMC Med. 2022; 20:375.

-

U.S. EPA, 2019. Section 10.2.5.1.

-

Shi L, Wu X, Danesh Yazdi M, Braun D, Abu Awad Y, Wei Y, Liu P, Di Q, Wand Y, Schwartz J, Dominici F, Kioumourtzoglou M-A, Zanobetti A. Long-term effects of PM2.5 on neurological disorders in the American Medicare population: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Planet Health. 2020; 4:e557-65.

-

Wilker EH, Osman M and Weisskopf MG. Ambient air pollution and clinical dementia: a systemic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2023; 381:e071620.

-

Gao X, Jiang M, Huang N, Guo X and Huang T. Long-term air pollution, genetic susceptibility, and the risk of depression and anxiety: a prospective study in the UK Biobank cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2023; 131(1).

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 5.2.11.

-

Pope CA, Ezzati M, Dockery DW. Fine particulate air pollution and life expectancy in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:376-86.

-

Bekkar B et al. 2020.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 12.5.1.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 12.3.5.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 12.3.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 10.2.5.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 12.5.4.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 12.6.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 12.5.3.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 12.3.3.

-

U.S.EPA. Integrated Science Assessment for Ozone and Related Photochemical Oxidants. April 2020. EPA/600/R-20/012. Section 3.1.4.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2020, Sections 3.1.5 and 3.1.6.

-

U.S. EPA. 2020, Section 3.1.7.

-

U.S. EPA. 2020, Section 3.2.4.1.

-

U.S. EPA. 2020, Section 3.2.4.3.

-

U.S. EPA. 2020, Section 3.2.4.6.

-

U.S. EPA. 2020, Section 5.1.3.

-

U.S. EPA. 2020, Sections 7.2.1 and 7.2.2.

-

Gao Q, Zang E, Bi J, Dubrow R, Lowe SR, Chen H, Zeng Y, Shi L, Chen K. Long-term ozone exposure and cognitive impairment among Chinese older adults: A cohort study. J Env Int. 2022; 160:107072.

-

U.S. EPA. 2020, Section 7.1.3.

-

Hao H, Yoo SR, Strickland MJ, Darrow LA, D’Souza RR, Warren, JL, Moss S, Wang H, Zhang H, Chang HH. Effects of air pollution on adverse birth outcomes and pregnancy complication in the U.S state of Kansas (200-2015). Sci Reports. 2023; 13:21476.

-

U.S. EPA. 2020, Sections 4.1 and 4.2.

-

Di et al. 2017.

-

Lim CC, Hayes RB. Ahn J, Shao Y, Silverman DT, Jones RR, Garcia C, Bell ML, Thurston GD. Long-term exposure to ozone and cause-specific mortality risk in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 200(8):1022–1031.

-

Bekkar B et al. 2020.

-

U.S. EPA. 2020, Section IS.4.4.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 12.5.4.

-

Liu J, Clark LP, Bechle MJ, Hajat A, Kim S-Y, Robinson AL, Sheppard L, Szpiro AA, Marshall JD. Disparities in air pollution exposure in the United States by race/ethnicity and income, 1990–2010. Environ Health Perspect. 2021; 129(12).

-

Lane HM, Morello-Frosch R, Marshall JD, Apte JS. Historical Redlining Is Associated with Present-Day Air Pollution Disparities in U.S. Cities. Environ Sci Technol Let. 2022; 9:345-350.

-

Nardone A, Casey JA, Morello-Frosch R, Mujahid M, Balmes JR, Thakur N. Associations Between Historical Residential Redlining and Current Age-Adjusted Rates of Emergency Department Visits Due to Asthma Across Eight Cities in California: An Ecological Study. Lancet Planet Health. 2020; 4(1):e24-e31.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey, 2022. Analysis performed by the American Lung Association Epidemiology and Statistics Unit using SPSS software.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 12.5.3.

-

Liu et al. 2021.

-

Mikati I, Benson AF, Luben TJ, Sacks JD, Richmond-Bryant J. Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status. Am J Public Health. 2018; 108(4):480–485.

-

Kioumourtzoglou M-A, Schwartz J, James P, Dominici F, Zanobetti A. PM2.5 and mortality in 207 US cities: modification by temperature and city characteristics. Epidemiology. 2016; 27(2):221-7.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 9.1.3.

-

Johnson NM, Hoffmann AR, Behlen JC, Lau C, Pendleton D, Harvey N, Shore R, Li Y, Chen J, Tian Y, Zhang R. Air pollution and children’s health—a review of adverse effects associated with prenatal exposure from fine to ultrafine particulate matter. Environ Health Prev Med. 2021; 26:72.

-

Yahzdi MD, Wang Y, Di Q, Wei Y, Requia WJ, Shi L, Sabath MB, Dominici F, Coull BA, Evans JS, Koutrakis P, Schwartz JD. Long-term association of Air Pollution and hospital admissions among Medicare patients using a doubly robust additive model. Circulation. 2021; 143:1584-1596.

-

Klepak P, Locatelli I, Korošec S, Künzli N, Kukec A. Ambient air pollution and pregnancy outcomes: a comprehensive review. Environ Research. 2018; 167:144-159. and identification of environmental public health challenges

-

Bekkar B et al. 2020.

-

U.S. EPA. 2019, Section 12.6.1.

-

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking - 50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2014.